Is Lactose a misunderstood Sugar or a Health Ally?” – A Look Back at Our Webinar

Although it is generally associated with digestive issues, lactose is actually a unique sugar that offers several health benefits. In this webinar, we explore the structure of lactose, its production, metabolism, and numerous health benefits.

Several external experts participated in this webinar: scientists Dr. Katia Sivieri and Dr. Rita Pessotti from Nintx, a private biotechnology company specializing in gut microbiome research, and Prof. Corinna Walsh, professor in the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of the Free State in South Africa. They shared their insights on lactose and its health benefits.

Definition of Lactose

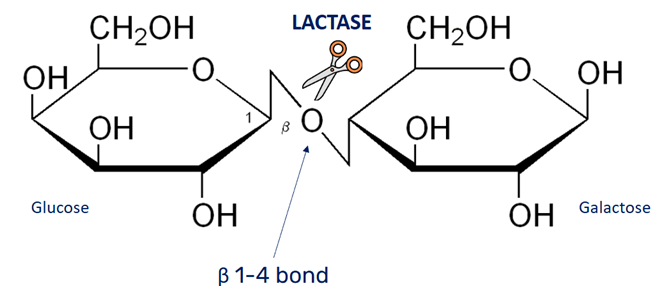

Lactose is a disaccharide, meaning it is composed of two sugar units: glucose and galactose, linked by a β-1,4 bond.

This bond is hydrolyzed by lactase, an enzyme found in the small intestine.

How Much Lactose Is in Dairy Products?

Lactose is the main carbohydrate in milk, with about 4.7 g per 100 ml in cow’s milk, making it the most abundant component after proteins and fats. Its content varies slightly depending on the animal species.

Lactose levels can also vary across dairy products, as processing and fermentation can reduce its amount. [1]

Powdered Lactose: Production and Industrial Applications

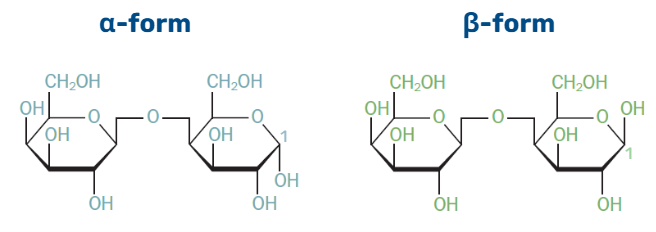

Lactose can exist in several states: crystalline or amorphous. The most common solid form is crystalline, while the liquid form is typically amorphous. In both states, lactose has two anomeric forms, α and β, determined by the position of the hydroxyl group attached to carbon 1 of glucose. This detail is crucial because it affects lactose stability once crystallized.

In milk at 20°C, amorphous lactose consists of about 38% α-form and 62% β-form. This balance depends on temperature, influencing solubility and crystallization behavior. As an ingredient, lactose is mainly used as alpha-lactose monohydrate, the most stable crystalline form, ensuring optimal shelf life and consistent performance in various food applications: chocolate, infant formula, sweetened condensed milk, fermentation substrates, confectionery, and processed meat products.

Manufacturing Process

The raw material is often milk permeate or whey from ultrafiltration, or liquid whey. The permeate serves as the base for crystallization. This key step converts amorphous lactose (α and β) into crystalline α-lactose under strictly controlled conditions: temperature, concentration, and pH. Crystallization begins when the solution becomes supersaturated, forming nuclei that grow into crystals.

Once crystallization is complete, the crystals are separated, washed to remove impurities, then dried on a fluidized bed to stabilize the structure and increase the proportion of alpha-lactose. Finally, they are ground and sieved to achieve the desired particle size, ensuring properties suited to industrial needs.

While the industrial process aims to control lactose structure and functional properties, understanding its metabolism in humans is equally essential to address issues related to intolerance and malabsorption.

Intolerance vs. Malabsorption

Lactose intolerance is often confused with malabsorption, but they are two distinct concepts. To understand this, we need to look at lactose metabolism.

In the small intestine, the enzyme lactase hydrolyzes lactose into two monosaccharides: glucose, an essential energy source, and galactose, involved in neural and immune functions. However, some unhydrolyzed lactose can reach the colon, where gut microbiota bacteria can hydrolyze and ferment it. The ability to digest lactose therefore depends not only on lactase but also on the diversity and metabolic activity of gut bacteria: some species ferment lactose efficiently, others less so, influencing individual tolerance. [2][3]

Lactose malabsorption is mainly determined by genetics. If you have the gene for lactase production, you are “lactase-persistent”: your small intestine produces lactase, enabling efficient digestion and limiting fermentation in the colon. Without this gene, lactase is absent or very low, and a large amount of lactose reaches the large intestine—this is malabsorption. But this does not necessarily mean intolerance. If your microbiota compensates by metabolizing this lactose, you experience no symptoms and remain tolerant. Conversely, if the microbiota cannot handle the lactose, excessive fermentation causes symptoms—this is intolerance. [4]

The Gut Microbiota: A Key Player and the Prebiotic Role of Lactose

The composition of the gut microbiota varies according to many factors: diet, age, stress, physical activity, medication use, or infections. Among these, diet plays a central role because it directly influences the availability of substrates for bacteria. In particular, certain dietary components, called prebiotics, selectively promote the growth of beneficial bacteria.

In 2024, the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics defined a prebiotic as “a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms and confers a health benefit.” In other words, dietary intake of prebiotics modifies the microbiota composition and its metabolite production, with positive effects on health.[5]

What about lactose? Within the Food Science, Nutrition, and Health Department at Lactalis R&D, a study was conducted to verify the first part of this definition: does lactose consumption lead to beneficial changes in gut microbiota composition? This study was carried out in lactose-tolerant subjects, the main consumers of milk. In these individuals, it is suggested that some lactose escapes hydrolysis in the small intestine and reaches the colon, where it may be fermented by microbiota bacteria. The goal was to assess whether lactose promotes a positive modulation of the gut microbiota in these individuals.

Using advanced intestinal simulation technologies, three doses of lactose (equivalent to half a glass, one glass, and two glasses of milk) were tested. Results showed a clear increase in the prebiotic index for all doses, with a rise in beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and a decrease in potentially harmful bacteria such as Clostridium. During a 14-day follow-up, the dose corresponding to one glass of milk led to positive changes in microbiota structure, notably an increase in Lactobacillus, Cicadibacterium, and Akkermansia—recognized indicators of good health. These findings suggest that lactose, like established prebiotics, can support gut health and enhance the nutritional benefits of dairy products.

To learn more about this study, watch the webinar where we collaborated with Nintx, a Brazilian company specialized in this field.

Glycemic Index, Calcium, and Cariogenicity

Lactose has a low glycemic index (≈46) compared to glucose (100) and sucrose (68), resulting in slower and more moderate glycemic and insulin responses after meals. This effect is partly explained by the gradual absorption of galactose, which also contributes to satiety. Studies show that lactose may reduce levels of ghrelin, the hormone that stimulates appetite, and thus decrease food intake by about 11%, making it a slow-release carbohydrate that could help with appetite control.

From an oral health perspective, lactose is the least cariogenic sugar. Unlike sucrose, which quickly lowers oral pH below 5.5, lactose ferments slowly, maintaining a pH close to 6 and limiting enamel demineralization. Research dating back to the 1970s, corroborated by recent microbiome studies, confirms its minimal impact on plaque bacteria. Combined with calcium, phosphorus, casein, and protective enzymes in milk, lactose contributes to milk’s cariostatic effect, promoting enamel remineralization.

Lactose also facilitates calcium absorption, especially in infants, by lowering intestinal pH and keeping calcium soluble—essential for bone mineralization during growth. In adults, data are more nuanced, but studies suggest that moderate lactose intake may improve calcium absorption in individuals with low intestinal lactase activity. Conversely, avoiding dairy products is often associated with lower calcium intake and an increased risk of fractures.

To learn more, watch the webinar where we collaborated with Prof. Corinna Walsh, professor in the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at the University of the Free State, South Africa.

Conclusion

In 2024, global lactose production reached 1.4 million tons, reflecting its widespread use not only in dairy products but also in chocolate, confectionery, infant formula, and pharmaceutical applications.

Lactalis Ingredients offers edible lactose from 60 to 200 mesh for food, infant formula, lactose-derived applications, and even pharmaceutical-grade lactose. From particle size distribution to different purity levels, Lactalis Ingredients covers a wide range of lactose qualities. All products are manufactured in Europe from raw materials sourced within the Lactalis Group, ensuring consistent supply, quality, and traceability.

Access the webinar replay, click here : Link to the replay

A question ? Contact-us !

Sources:

[1] Ciqual, 2024

[2] Guerville and Ligneul. Cahier de Nut & Dietétitique. 2024

[3] Forsgard. Lactose digestion in humans. Am J Clin Nut. 2019

[4] Ganzle. Chapter 4. Lactose- a conditional prebiotic. Lactose. 2019

[5] Hutkins, Nature Reviews, 2024

All article:

Anguita-Ruiz, A., Vatanparast, H., Walsh, C., Barbara, G., Natoli, S., Eisenhauer, B., Ramirez-Mayans, J., Anderson, G. H., Guerville, M., Ligneul, A., & Gil, A. (2025). Alternative biological functions of lactose : a narrative review. Critical Reviews In Food Science And Nutrition, 65(31), 7444-7457. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2025.2470394

De Cassia Pessotti, R., Guerville, M., Agostinho, L. L., Bogsan, C. S. B., Salgaço, M. K., Ligneul, A., De Freitas, M. N., Guimarães, C. R. W., & Sivieri, K. (2025). Bugs got milk ? Exploring the potential of lactose as a prebiotic ingredient for the human gut microbiota of lactose-tolerant individuals. Nutrition Research, 136, 64-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2025.02.006