Is there a risk from protein over-consumption?

Proteins can currently be found in a wide range of product categories. In addition to animal proteins, such as meat, fish and eggs, which are the traditional source of protein, complementary sources are a steadily growing sector. What is more, any product can be protein enriched these days. While consumers have a growing appetite for proteins, should we be worried about protein over-consumption?

Why is it important to eat proteins?

Proteins, like the two other macronutrients (lipids and carbohydrates), are a source of energy.

Proteins are composed of a set of amino acids, the order and quantity of which determine both their structure and their function.

There are twenty proteinogenic amino acids, in other words amino acids that are used for the manufacture of proteins.

Of these, nine are said to be essential, as the body cannot synthesize them. They must therefore be provided to the body in sufficient quantity through nutrition in order to meet physiological needs.

The others are called non-essential as the body is able to synthesize them, although they can become essential in certain physiological or pathological situations (growth, wound healing, infection, etc.).

Proteins have a fundamental role in the human body at every stage of development

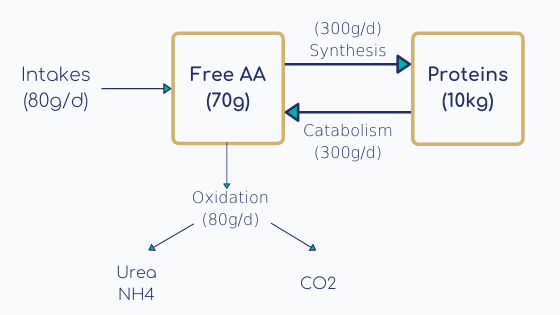

The body of the average adult male (70 kg) contains 10 kg to 12 kg of protein, of which 40 % is found in muscle, which is thus considered to be the main storage location.

This protein mass is renewed at an average rate of 3 % of body weight per day, though the exact figure varies according to the type of protein. For example, renewal is very rapid for liver proteins and very slow, if not inexistent, for lens proteins.

There is no protein store in the body, as there is for lipids, for example. Dietary intake must therefore cover these protein renewal needs (on average 10 % à 20 % of the energy ration) and the synthesis of nitrogen molecules that are essential to the functioning of the human body.

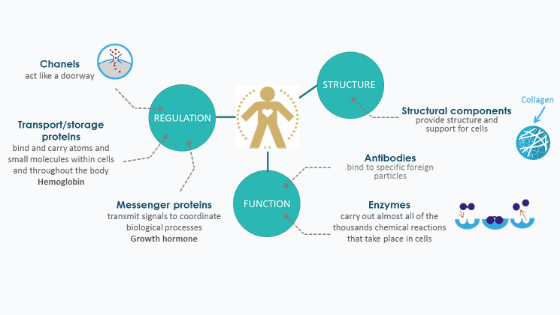

Proteins participate in the majority of physiological functions: they have a structural role (for example collagen), a functional role (albumin and insulin) and a contractile role (myosine, for example), as well as a role in the immune system (for example immunoglobulins)… Proteins are involved in the renewal of muscle tissue, bone matrix, and the skin.

In humans, the digestion and absorption efficiency of proteins is dependent on the protein source. Milk proteins have the best bioavailability: 95 % of proteins ingested are properly absorbed and assimilated by the body, followed by meat proteins (94%) and, lastly, plant proteins (90-91%)[1].

Figure 1: Role of proteins in the body

Proteins therefore have a fundamental role in the human body at every stage of development, and in adults constitute a non-negligible proportion of body mass. To ensure the proper renewal of this protein mass, the diet must contain sufficient amounts of protein, in particular essential amino acids.

What are the dietary recommendations for proteins?

The recommendations for average needs aim at a neutral nitrogen balance. In France, they have been set at 0.83 g/kg/j for healthy young adults by ANSES (the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety).

That figure assumes the protein intake to be of good quality. The essential amino acids must therefore be present in sufficient quantity.

The protein recommendations were published in 2007 by AFSSA (the French Food Safety Agency) and in 2016 reiterated by ANSES[2] on the basis of nitrogen balance studies and in accordance with North-American (IOM 2005) and international (FAO 2007) recommendations.

The Committee of Experts established three categories of intake[3] for non-obese, non-athletic adults under the age of 60, with normal kidney function and no restrictive diet (the average calorie intake being set at 33 kcal/kg/d):

-

-

- Adequate intake: 0.83 to 2.2 g/kg/d

- High intake[4]: 2.2 to 3.5 g/kg/d

- Very high intake: > 3.5 g/kg/d

-

ANSES recommends that protein consumption be between 10 % and 20 % of the total energy consumed.

What are the risks associated with protein deficiency?

Proteins in the body undergo constant synthesis and degradation. In normal conditions, there is an internal balance between food intake, synthesis by the body and excretion. The term “nitrogen balance” is used. This balance is achieved if the quantity of nitrogen ingested equals urinary, fecal and skin losses. Certain pathological conditions can lead to a negative nitrogen balance.

Figure 2: General metabolic pathways in humans

Nitrogen deficiency can cause atrophy due to muscle wasting, hypoproteinemia with the risk of edema formation, deficiency and malnutrition. It should also be noted that when fasting, the body breaks down its proteins, in particular in the muscles.

Is there a risk from protein over-consumption?

The possible dangers of excessive consumption of proteins are a subject of debate. In 2007, AFSSA declared that there was no risk to health at up to three times their recommendations.

One risk of consuming too much protein is a potential overloading of the kidneys. When the protein synthesis pathway is saturated, excess amino acids are deaminated, producing ammonia. This molecule being toxic for the body, it is converted into urea, hence an increase in ureagenesis and therefore uremia[5]. Just how much the maximum capacity for ureagenesis might be is a question that comes to the fore when assessing the risks of over-consumption of proteins.

But studies that deal with the consequences of a high-protein diet are somewhat biased. The data from these studies was obtained from subjects who were unsuitable for high intakes, which logically results in a relatively low threshold for maximum ureagenesis capacity.

ANSES, in its recommendations, thus set an upper limit without any conclusion relating to an upper safe limit that minimizes the risk of weight gain.

There was no risk to health at up to three times their recommendations.

While no study to date has been able to prove a direct risk from over-consumption of proteins, it is still worth looking at actual protein consumption compared with scientific recommendations.

In developed countries, daily consumption is estimated to be between 100 g and 120 g of protein per day, 35% of which is of plant origin. That is equivalent to a daily consumption of 1.4 to 1.7 g/kg. For example, average daily protein consumption in France is 83.2g, i.e. 16.8% of daily energy intake[6]. The consumption of proteins in developed countries is therefore within the intake recommended by ANSES.

In developing countries protein consumption is lower. Intake is estimated to be 40-50 g per day, i.e. 0.6 to 0.7g/kg, 85 % of which is of plant origin.

In view of the daily protein intake in both developed and developing countries, it would seem that over-consumption of protein is rare.

Body proteins constitute a capital that must be maintained. They need to be renewed constantly in order to sustain that capital and thus quality dietary intake is essential. There is currently no documented risk associated with over-consumption of proteins. On the other hand, the type of protein in the diet is of consequence, since over-consumption of red meats may represent a cardiovascular risk.

Requirements should therefore be met through the consumption of both animal and plant proteins. However, the quality of these proteins needs to be taken into account, since certain dietary proteins provide the essential amino acids. Proteins of animal origin, in particular proteins from milk, offer an advantage when it comes to meeting the needs of the body, especially at certain key periods of life, such as during pregnancy, growth, ageing and in the context of pathologies.

Sources:

[1] Oberli et al, 2015; High True Ileal Digestibility but Not Postprandial Utilization of Nitrogen from Bovine Meat Protein in Humans Is Moderately Decreased by High-Temperature

[2] Opinion of ANSES – Referral No. 2012-SA-0103

[3] AFSSA. 2007. “Rapport de l’Afssa relatif à l’apport en protéines: consommation, qualité, besoins et recommandations“

[4] Determined from the maximum capacity for ureagenesis in adults (adult male weighing 70 kg).

[5] https://www.anses.fr/fr/system/files/NUT-Ra-Proteines.pdf

[6] INCA3 survey (2014-2015), handled by ANSES